Summary

Getting started in consulting electric motor design. The title says it all. Just my condensed thoughts on the topic.

Colossal Disclaimer

I. Do. Not. Teach. Consulting.

There, I said it. I mean, if you take one thing out of this text, please make it this – the best doers are not generally the best teachers.

People miss this so often. If you want big biceps, go ask the person who has coached many people – preferably from your background and characteristics – get big biceps. Don’t go ask the the person who has big biceps.

That said, I do get asked this question a lot, so I thought I’d save some of my time AND hopefully help a few souls out in the process, by writing down a few thoughts on the topic. (Note: I’m coming down from my lunch-prosecco while writing this, so terms and conditions may apply.)

Obvious things

Now, these may not be obvious to you which is fine. But, they are obvious enough for me to almost forget writing about them, so here’s a brief list.

- Definition of design consulting here: You do electric motor engineering work of some kind, any kind, and get paid in money. You are not an employee.

- You bill either based on realized hours / days / weeks / months, or for the project as a whole.

- You bill either after the projects completion, or in pre-agreed intervals. Both have their place.

- A retainer is an arrangement where you guarantee certain availability for a certain monthly price. I’ve never had (or pushed for) one, and avoiding the situation where you simply sell your hours at a discount obviously requires a certain level of trust, but the situation can be mutually very beneficial under the correct circumstances.

- You often sign an NDA. Get a lawyer to read it if needed (and this here is not legal advice), and make sure it defines what it is you cannot disclose, and makes the typical caveats for court orders, accidental leaks, information coming to your knowledge via other non-restricted means, etc.

- NDA-style discretion on your part should be given, regardless of what you have signed.

- Non-competition clauses are rare but not completely unheard of. Make sure you account for them in your pricing and current business prospects. You are not an employee.

- It is common to expect that whatever invention (or IPR of any kind) you make within a project belongs to the client, whether or not you have it in writing or not.

- If you do want to make an exception, put it in writing.

- Common ways of getting work:

- Word of mouth. Takes a long time, but once you get rolling it can be great.

- Online presence. For the love of everything good, have something to say other than repeating buzzword-of-the-month’s marketing claims with a stock photo.

- A plain old website seems to work way better than expected.

- Outreach: sending emails, LinkedIn messages, and making phone calls.

Update: Where to find clients

Disclaimer: I will be committing two cardinal sins of my own book of ethics very shortly. I’ll be advising you the reader to do what I haven’t personally done, and I’ll be giving a hand-wavy non-answer.

So, where and how to find clients?

aNyWhErE.

There, the annoying non-answer out of the way. If it’s good enough for folks online giving advice on dating, it’s good enough for me giving advice on consulting. Just like you can find aesthetically and ethically pleasing members of your preferred gender anywhere, you can find consulting work anywhere.

You just probably won’t.

My first-ever client actually found me from my blog, that I had been running perhaps one or two years at the time. My second client found me in a small university-industry networking poster session (just two research groups who pretty much invited their past students plus their other industry contacts).

One of my two first attempts at outreach resulted in work. The other essentially told me they have an engineering boyfriend and politely told me to frak off. (See the dating analogy above, and the section on luck below). They still ended up my client, 8 years later. Funny how that works.

Now the second part of the poor advice, on what to do that I never really did. (So please put a healthy sprinkle of salt on everything you’ll about to read.)

In the beginning, active outreach is probably the best return on invested time. Inbound marketing like a website, LinkedIn presence, and word-of-mouth is more like monthly investing on index funds – it will pay itself off in the long run, but in the beginning it’ll get you zip-all. There’s a paragraph on timing further down this text, but the summary is probably this: it takes 9-ish months to see if you can get enough work via active outreach, and closer to 3 years to figure out if your passive funnel can sustain you.

Now, for doing active outreach, probably the easiest single thing is periodically letting everybody know you are available for this type of a work on LinkedIn. The hit rate will most likely be very poor, but at least it costs nothing in terms of time and effort and can keep you on at least someone’s mind. Third time applying the dating analogy: it’s probably a good idea to not appear desperate at all here.

Also, it might be a good idea to let all of your existing contacts know you are available, via more-tailored private messages. I’m not talking about every LinkedIn connection you may have, but people who you have at some point worked with, or at least someone that your professor knows.

Again, keeping things light and low-effort for everybody could work. You could for instance ask if they have in the past used contractors like you, or if the person you are speaking to knows if they have processes for that in the first place.

Finally, the third, and the most involved approach would be to suggest an actual meeting to somebody. You can do this independently, or you can first filter people for this stage based on the results from the first two steps.

Now, the internet is full of advice on discovery sessions and road-mapping sessions and whatnot. The idea, apparently, is to figure out what the client’s problems are and where you could help.

None of those work, as such, without modification, for electric motor design in my experience. The above advice is tailored for software folks or management consulting folks, where the design space is considerably larger. You probably won’t be suggesting engineering solutions to high-level business problems, until you have at least a decade or two experience and have actually seen a product or two to the market.

Nonetheless, it might not be a good idea to sit down over a coffee to find out what kind of engineering problems they are currently facing, and seeing if there is some overlap with what you can do. And, listing out what you can do is not a bad idea at all – it might well happen there’s something very obvious to you that the client has not even considered.

You can even frame it as something you are doing for yourself – i.e. finding out what people like <the one you are talking to> are generally facing, and finding out what you could be working on in the future. It depends on the culture; this approach might make it easier for the other party to accept, i.e. when they don’t expect you to be pestering them with sales pitches for months to come. (And please don’t do so.)

Finally, you could even offer to do a practice project for free. I think every engineering team has bunch of cool ideas or nasty problems they would like to see explored, but really can’t spare the time. Doing a literature review and maybe some nice simulations (everybody likes nice plots!) probably wouldn’t hurt.

Now, framing the free part properly is important here. Offering your time for free is something to be avoided, generally. But, being brutally honest that this is your first rodeo, and you would like to see how this kind of a work suits you – that could work. You should probably specify the scope of the project you are looking for, for instance ’40 hours of work, for which you would be charging 4k-5k in the future’.

Update: On luck and cross-section

My personal worldview is that way more depends on luck than we are generally willing to admit. I don’t mean winning the lottery kind of luck; I mean having been born to a decent family with a good capacity for intelligence of the mathematical kind, having a certain natural tendency of working both smart and hard, having picked up a good major at the university without giving it your 100 % of thought – stuff like that. Happening across an engineering manager looking for a consultant certainly helps, too.

From a more scientific point of view, people in general tend to attribute more of their success to their own capabilities than is rational, and be more inclined to blame any negative event on their surroundings. Both are probably healthy in moderation, but both can also make you an insufferable caricature of the person if taken to the extreme.

Now, the actual consulting tangent: I’m a fan of the concept of ‘luck surface area’, or luck cross-section for the more nuclear-engineering minded person.

Meaning, you can still take steps to maximize your probability of success (whatever that may mean for you right now in this specific matter), while still acknowledging that there is a random element.

For instance, actually, you know, letting people know you are available for consulting highly increases the changes of somebody reaching out to you for consulting. Even better if those people are actually working in engineering.

You get the idea, making the good kind of noise, reaching out to people yourself, perhaps going to a scientific conference or Coiltech, all can work.

How good do you need to be

Advice on how good to be, or how good you need to be for consulting in particular, is all over the place. And that’s somewhat for a reason – it depends.

Obviously, you can’t suck too bad – charging money for it would be immoral in my eyes, and might be illegal under certain conditions.

But beyond that, the entire range from ‘good enough’ to ‘the best there is’ has its own pros.

The lowest end – being just good enough – is comforting for anybody just starting out. You don’t need to be the best motor designer in the world – you only need to be good enough for what the client needs (and your pricing), and available when the client needs it (within your own well-defined boundaries, mind you). That’s all, that’s enough, and the client will be happy if you do the work to the best of your abilities and professional standards.

The upper end, being the best there is, is obviously beyond the reach of everyone minus one. However, being in the top-whatever percentile is a worthy and possibly-reachable goal. Being the best you can be is a very good goal (as long as you keep it within the realms of sanity).

Besides, being extremely good is, well, good for business. The author Cal Newport has a book somewhere around the topic. I rarely find buzzy self-help books to be much beyond mental masturbation, but his work is solid. Go read everything he has written.

Maybe don’t call it freelancing

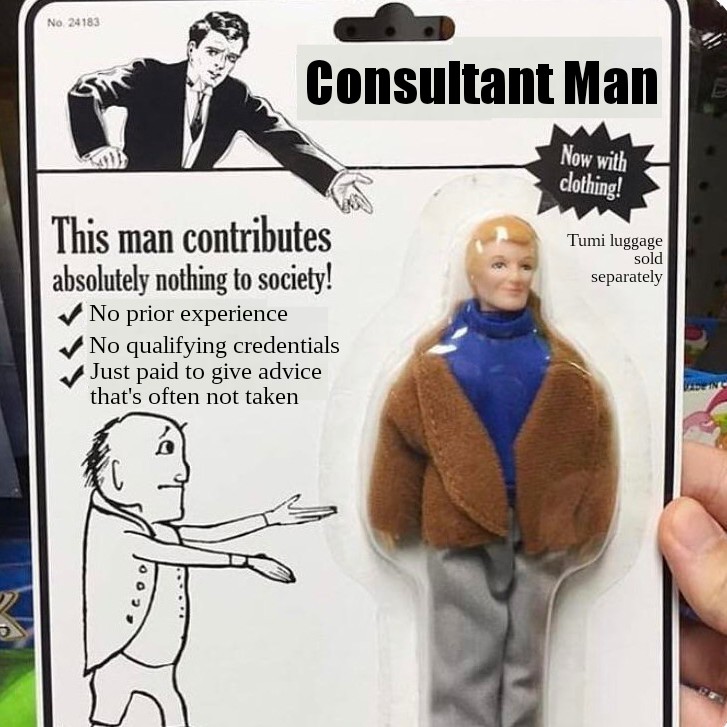

It’s common advice to not call yourself a freelancer. The reasoning is that a freelancer is a commodity, someone to choose from a large pool of candidates, someone who bills by the hour or minutes, and someone who transforms (detailed) instructions into a(n unsatisfactory) end result. By contrast, a consultant is more of a trusted advisor, someone taking a much more involved role, and obviously rarer and more expensive.

This probably doesn’t apply to everybody. Some people certainly associate the word ‘consultant’ with suited pr*cks who march in with a dozen junior associates, fire a bunch of people, and actually solve precisely frak-all.

Point being, being able to describe (and decide) what you do is kinda important – I will return to this topic multiple times.

Sidenote: I want to believe (that’s an accidental X-Files reference by the way) that the word freelances stems from the words free (duh) and lancer, i.e. an armored cavalryman armed with a lance. A knight in essence, without the title, and their allegiance measured in coin rather than oath. In any case, please don’t follow this train of thought to the more belligerent direction – calling yourself a sellsword, a mercenary, or a soldier of fortune is an awful idea. War can make for good entertainment, and has done so since the dawn of writing and most likely way before, but war itself is horrible beyond words, and most people like to disassociate themselves from anything remotely related.

Things take time

This needs to be said first. Getting started on anything takes time.

How long, depends on where you start from. If you have 40 years of experience working in client-facing roles in the industry, things will probably be quite smooth for you. If you’re straight out of high school, not so much, likely.

Generally, numbers between 9 months and 3 years get thrown out a lot and seem to match my experience.

And for a good reason: 9 months is probably enough to figure out whether or now your consulting idea is feasible or not – provided you are active and willing to pick up the phone or at least type out enough outgoing emails. That said, filling your pipeline via more passive means probably takes closer to a few years.

Things take time Pt 2

Even with your pipeline filled out – having projects agreed on – there’s normally still time between execution and having the moneyz comfortably on your bank account. At the minimum, expect billing every 1 to 3 months, with a payment term of 90 days – that’s 4 to 6 months between the final signatures and actually getting paid. And that’s after getting to the point of final signatures – please see my previous point.

The important point here is making sure your personal finances do survive the transition period. In business terms, we (or they, I rarely deal with the buzzy-ness aspects myself) call this having enough runway.

On depth and scope

If you’ve ever read two words about sales or marketing, you’ve probably come across the term positioning or its various synonyms. Simply put, positioning means (something) like figuring out what you’re selling and for whom, and then designing all your marketing activities (or any activities aimed at getting paying clients) around it.

Again, easier said than done. What gets repeated ad infinitum is that the more specific you are – in terms of what and for whom – the easier it is to sell your services.

The flip-side, that’s for some reason often left unsaid, despite its obviousness, is that the fewer people (in the end, it’s still people making the decision) actually fit your definition.

Trying to sell electric motor design services, servicing electric motors, actual motors, and finally gardening and dog-walking in the same message most likely wouldn’t work. It might, and it might even stand out due to being so hilariously across the board, but it might just as well repel possible clients. All are valid businesses, by the way, just for completely different people, or at least different roles of the same people.

On depth and scope Pt 2

The same principle also applies to the electric motor design as a business, as a whole. Compared to, say, sales or marketing, motor design is already a niche business.

Which is both a blessing and a curse. Everybody (as in every business) needs and is interested in sales and marketing. Everybody (at least compared to the number of motor designers) is offering sales and marketing, and just selling ‘marketing’ is probably nowhere near specific to make you stand out enough to ever be hired.

By contrast, just being an ‘electric motor designer’ for hire might.

Specializing in, say, getting 3/4-finished designs into series production might be an even better choice, or perhaps not. Again, it’s easier to sell compared to just being an all-around generalist motor designer, but again the number of people interested in specifically that and right now will be smaller.

Don’t go too BS:ssy

If you have had the displeasure of reading (or watching, if that’s your thing) some of the more recent material on marketing, sales, and positioning online, you have probably come across this phenomenon.

You know, simply listing what you do is bad – you have to tell how it helps the client. That’s the general wisdom, in that particular bubble on the Internet.

And like everything else on the internet, things get taken waaaaaaaay too extreme.

I mean the ‘Linkedin job description’ type of sales pitch, obviously. Stuff like ‘I help C-level executives in small-to-medium size businesses accelerate the transition to a carbon-neutral future‘. Umm, yes, cool. So that do you, you know, actually do? Oh, I’m an electric motor design consultant.

Granted, most of the advice online has been written for people in other lines of work, most commonly either marketing, sales, or software. Going way more specific than a marketer makes sense.

I’m not sure going more specific than a motor designer does. If you actually do specialize in thermal design or vibrations, by all means go for it and see if it sticks! My point is, consider not being too fancy, at the cost of clarity.

Say no often enough

Now, this is obviously something of a luxury. If you are (good as) starving, and somebody asks you to clean their metaphorical gutter for a dime, you’d probably do it.

But, once you have some financial buffer and some freedom to choose, it often pays out to be picky. This is true for two aspects at least.

First of all, it’s rather common knowledge across pretty much any trade that the cheapest clients are usually the worst. Now, it’s perfectly fine (in my eyes – some will certainly disagree) to compromise somewhat if the other party has clear budget constraints, maximum project sizes dictated from above, or stuff like that. However, someone asking for discounts ‘just because’ and then counting every cent rarely is a pleasure work with, at least in a contractor-type arrangement.

If you find yourself in a situation where you would have to compromise on your prices a lot, consider either dropping the case or doing it pro bono. Doing stuff for free generally is nothing but an endless time-sink; however helping a Formula Student team is cool. If I do free stuff, I generally reserve the right to showcase the project for marketing purposes, which is usually not cool by default with your generic corporate client.

Secondly, it’s a good idea to be upfront if you have no idea how to do something, or have never done it before. I know, I know, the internet is full of quotes from Great Master This and That about how you should just say yes and then read three books on the topic and then just deliver it.

Don’t do it. Just don’t.

And by the way, reading three or a hundred books is nowhere near enough to competently do anything. It’s perfect for getting something to talk about over a beer or at a dinner, and you definitely should passively learn new stuff to talk about, but actually learning to do requires the doing part.

Don’t go too far out of your comfort zone

Which brings me to my next point – don’t go too far beyond your professional comfort zone.

I know, again I’m contradicting the nameless masters of the old. Life begins at the edge of your comfort zone and all that.

It does – on the edge. As in, still near the edge. Not miles away from it.

Again, you definitely should be constantly learning new stuff (and doing your old stuff better) as you mature professionally. However, you should still be building on your existing foundations, or at least immediately next to them.

Trying to do something completely new very likely results in a disaster with burnout-level stress for everybody involved.

Consulting doesn’t scale

The Startup Scene, with all caps, is all about whether something scales or not, ad nauseam. Granted, most very definitions of the term ‘startup’ do include a business aiming at massive growth, but I do still think they receive far too much attention compared to solo entrepreneurship or more-traditional small businesses.

Still, consulting alone as a business model does not really scale. You won’t be earning tens of millions (EUR, or USD for now still) a year doing consulting.

Granted, the ‘consulting-centered approach’, with public speaking, courses, books, or other products does help with this somewhat. Still, the only way to really move beyond supplementary-level extra income is to hire a bunch of people. Never done it myself, but the general rule of thumb is that you need at least four employees to make of for the extra hassle, after which what you really are is a manager or a CEO – not a consultant any more.

Do you need to scale?

Consulting does not scale. What I mean, it doesn’t offer a small change (let’s be realistic, all startups fail – to a statistically significant degree) of colossal future income.

What it does offer is a rather nice change of rather nice income right now (comparatively speaking, remember how things still take time).

Slow and steady does win the race quite often. Billing 6k or 10k or 15k every month does not make you a multimillionaire in a few years, but keeping those numbers up month in and month out does add up.

But the same principle does also apply to the other extreme – being a salaried employee. Consulting is not risk-free, and your monthly income and even yearly income will vary. Getting a modest salary every month may very well beat having a stellar year followed by two not-so-great ones.

On risks

Risks are difficult to evaluate.

Well, consulting vs a startup is rather easy. Startups have a small probability of very high income, and a very large probability of exactly zip all. Nothing in between as a first approximation.

Consulting has a zero probability of colossal income, and a very high probability of decent-to-nice income.

Consulting vs a salaried position is a more difficult beast to evaluate. Were there no risk of unemployment, it would be easy. A salaried person would have a 100 % change of earning their salary, and 0 % change of nothing else, apart from the semi-annual raise. Like the jobs were in the best of times and best of positions.

As things stand, a salaried person does have a non-zero change of being fired (I dislike the term ‘let go’ – it’s ‘push out’ in most cases), after which they have a X % change of finding a Y-salaried new job in Z-months. Very, very difficult to evaluate with anything resembling confidence.

But, in general, consulting represents a diversified source of income. If you do your job well, I’d wager that having any extended period of no billable work (hours, days, projects, whatever your scheme of billing is) is quite unlikely, catastrophic economic upheavals aside. Significantly less likely than a salaried person being laid off, I’d wager.

At the same time, having poor periods – multiple months of not so good averaged monthly income – is more likely.

| Income | Employee | Consulting | Startup |

| None at all | Moderate | Very low | Very high |

| Poor | Nope | Moderate | |

| Decent | High-ish | Very good | |

| Nice | Better than good | ||

| Colossal | Nope | Very low |

How much to charge

Short answer: around 100 EUR per hour, or equivalent. There’s lots of variation, but that’s a good order of magnitude to start from. 20 EUR is far too little, and pulling 500 EUR is difficult. It can be somewhat lower than 100, especially for longer projects with guaranteed monthly income. It can be somewhat (1.something to 2-3x) higher, especially for shorter projects and/or clients in countries with generally higher engineering wages. The shorter and higher-level the work is, the higher your charges can be. A hand-wavy talk with lots of name-dropping could be multiple times that, and a public speaking gig easily dozens of times, at least if you don’t spend too much time preparing.

Long answer:

As much as you possibly can, duh.

If you’re never getting pushback, aka complaints about being too expensive, you are leaving money on the table.

Both are common advice, and not bad advice at all. Especially here in Finland, the more-traditional advice for aspiring entrepreneurs has been to charge less than their competition, i.e. making price the only point of comparison. I already told you something about this.

There are also plenty of calculators online, for determining your hourly or daily rate. In my opinion, if you can’t figure out that math yourself, you probably have no business designing, well, anything engineer-y.

But, there are some pitfalls that may be non-obvious. The first one that you should not work 52 weeks a year. Leave a few weeks off for planned vacations, and then at least two more for getting sick, plus other unplanned stuff.

Next, don’t count on 8 hours of effective (billable in some kind or other) work per day. There’s overhead – often plenty of it. 50 % is a good estimate to start with. Once you get rolling, you can work on pushing it up.

Finally, remember to account for the inevitable economic crash. Something like every 4th year being worse than the others. Not all-zero, most likely (remember the fancy income distribution table), but worse.

So there you have it, between 40 and 48 weeks of work each year, 20 hours of effective work each. Next, decide how much you want to earn per year, add all the compulsory expenses and taxes, and you have your number.

Crucially, also do the math for how much you need to earn – that’s your minimum level. Something that’s good to keep in mind.

Hourly vs fixed-bid

You can bill by the hour (any practical increment of your choice). I have no hard feelings on this topic, and no clear winner in my mind. There are simply some things that you must bear in mind.

The upside of fixed-bid projects is that your effective hourly rate can be very high. There’s little change you could get a proposal with 1k/h accepted – however finishing a 10k project in 10h is within the realm of possibilities.

Obviously, the idea here isn’t to cheat the clients out of their money – the idea is being able to reliably deliver high-quality work worth its cost to the client.

Thus, opportunities for truly colossal markups are rare in my eyes.

Nevertheless, fixed-bid projects still are often mutually beneficial. Many clients do prefer a cost known in advance. And, since you are no taking the all the risk of the work being of higher effort than expected, you are definitely entitled to charge a premium for it. And, as mentioned, the client ultimate cares of if your output is worth the money or not – not how hard you worked for it.

On the flip side, hourly-based billing does have its place. Many projects are exploratory in nature. If you don’t even know the destination in advance, let alone have a well-defined map there, you can’t really estimate how long the travel will take.

One final note on fixed-cost projects: project duration (or efforts) has a long-tailed distribution. Something like 3 or 5 or 10 percent of projects will take wayyyyy longer than originally estimated. Your mileage may vary, but this is again something that you must take into account.

Check out EMDtool - Electric Motor Design toolbox for Matlab.

Need help with electric motor design or design software? Let's get in touch - satisfaction guaranteed!

One thought on “Getting Started in Consulting – Electric Motor Design Version”